Who are the Çingene and how have they preserved the culture of Crimea?

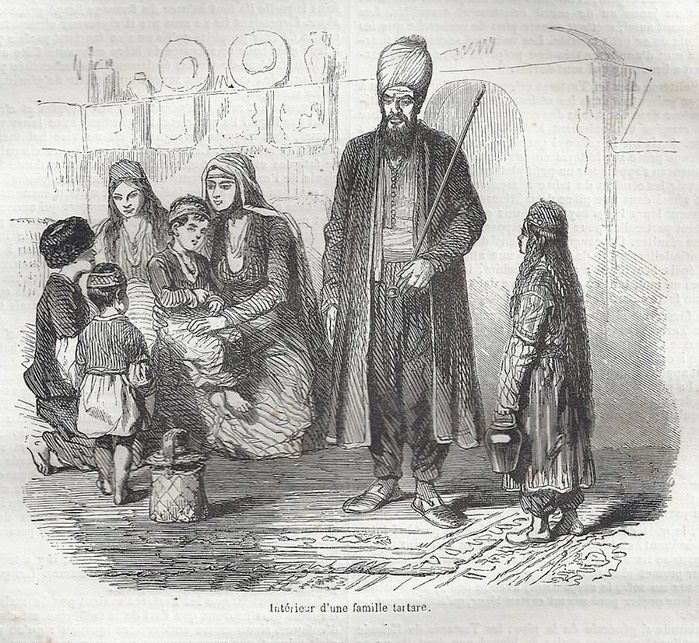

They are called Çingene or Krymy. Their religion is related to Islam, and their language contains many Turkic words. They consider Crimea their homeland, although they are scattered in different parts of Ukraine. Crimean Roma, Krymy or Çingene, are one of the numerous Romani ethnic groups that inhabited the territory of the Crimean Peninsula. Researchers still debate where Crimean Roma specifically came from. However, the most plausible theory is that the Çingene came to Crimea from the Balkans.

There are other theories as well: Crimean Roma could have originated from modern-day Moldova, Southern Syria, or Persia. However, it is important to note that the migration of Crimean Roma to Crimea did not happen in a single period and certainly not from a specific locality. The lengthy process of migration resulted in the mosaic nature of this ethnic group, contributing to the mystery surrounding the origin, way of life, and traditions of the Çingene. In general, the basic stages of the formation of Crimean Roma took place on the Crimean Peninsula, hence the name correlating with this region. Furthermore, their linguistic dialect is close to the language of Crimean Tatars, allowing the Çingene to communicate effectively with them. This is unlike, for example, the Roma-Lovari ethnic group residing in the Zakarpattia and Lviv regions, with whom communication might not be as seamless.

How did the Çingene interact with the Crimean Tatars?

Today, much can be heard about Crimean Roma beyond Crimea, as they predominantly inhabit the Kherson region, Dnipropetrovsk region, and Odessa region. In Crimea itself, there were entire districts and areas where Crimean Roma lived. Even now, a significant number of these subgroups continue to reside on the peninsula. In the past, with the arrival of Çingene in Crimea, they were typically settled on the outskirts of large cities such as Karasubazar (Bilohirsk), Akmescit (Simferopol), Bakhchisaray, Ermen Bazar (Armiansk), Kezlev (Yevpatoria), Kafa (Feodosiya), and Eski-Qirim (Old Crimea). Later, in these areas, Crimean Roma formed their own distinct quarters, which came to be known as " Çingene mahallesi".

Roman Kabachiy, a historian, journalist, and researcher of migration processes and ethnic minorities, notes in one of his studies in the journal "Kunsht" that the fact of the compact residence of this population group in Crimea did not isolate them or separate them from the entire Crimean Tatar population.

On the contrary, "The fact that Crimean Çingene were ethnically distinct from the majority of Crimean Tatars did not significantly differentiate their status from the 'indigenous' Muslim population. They were closely integrated into local communities to the extent that, by the 19th century, most had forgotten the Romani language and spoke Crimean Tatar. The dialect of the Crimean Roma, unique within Ukraine and the Kuban, belonged to the Balkan type of Romani dialects. However, on the Crimean Peninsula, the language of the Nogais, the steppe Crimeans, exerted the greatest influence on it."

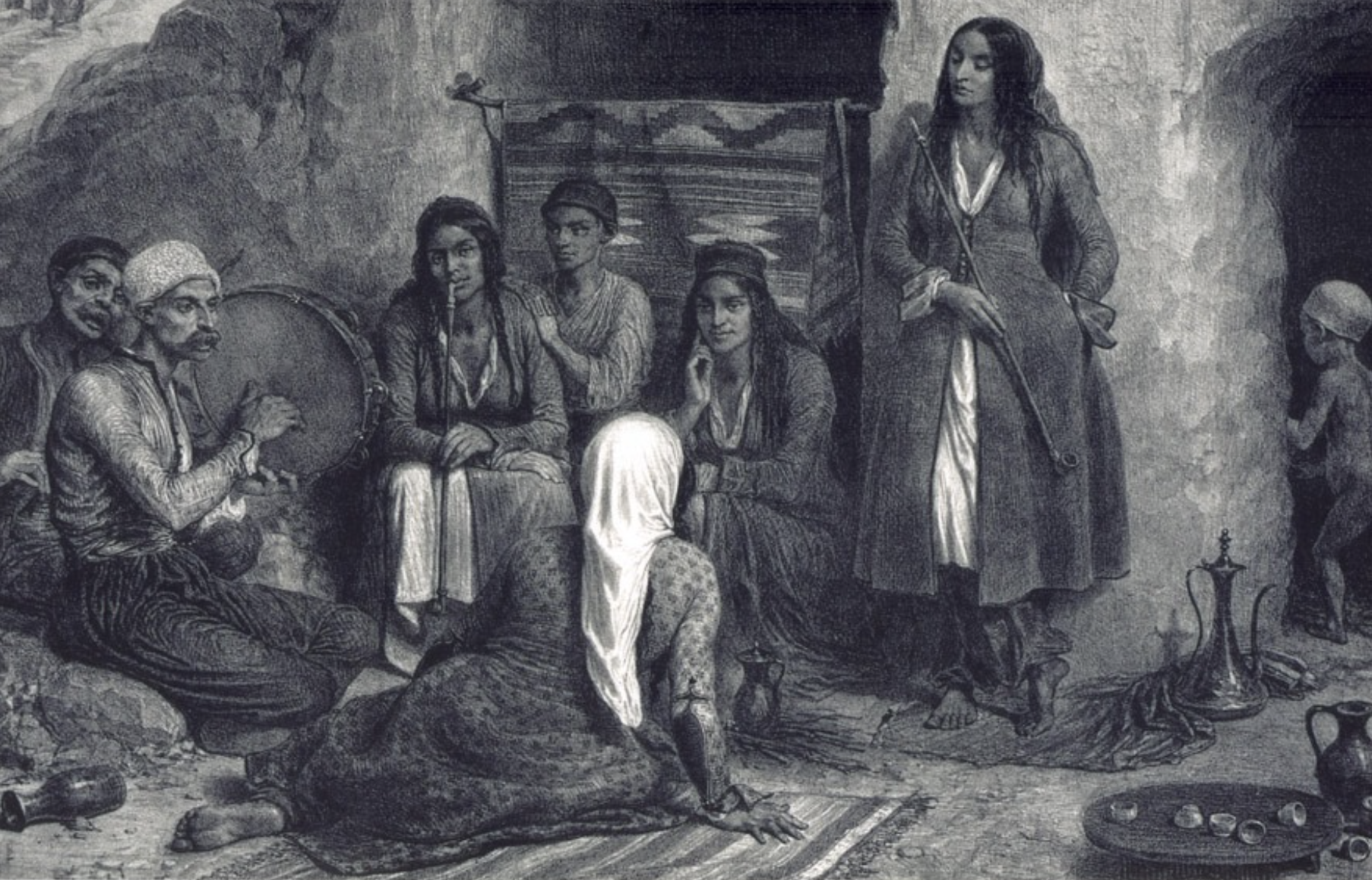

Living in the Crimean Khanate for centuries, Crimean Roma never felt oppression or discrimination. They were not treated with disdain. Instead, they were able to lead a settled or semi-settled way of life, engaging in their preferred crafts such as jewelry making or music. The only requirement, as for other residents of the Crimean Khanate, was to abide by the laws of the state at that time. The most widespread profession among Crimean Roma was jewelry making. The wealthier ones opened their own jewelry workshops, both in their own neighborhoods and in Crimean Tatar quarters. Jewelry stalls or even full-fledged workshops could occupy entire streets. Therefore, as we can see, Crimean Roma had the full right to manufacture and sell their products on an equal footing with all the inhabitants of the Crimean Khanate.

How the Çingene saved the music of the Crimean Tatars.

Another significant aspect of the shared history of Çingene and Crimean Tatars is music. During this stage of history, Crimean Roma played a crucial role in preserving the Crimean Tatar musical heritage, thus preventing the loss of authenticity in the music of the Crimean Tatars. According to Amet Bekir, a community activist and manager of the Crimean Tatar Cultural Center in Lviv, Çingene themselves saved and later revived the musical tradition in Crimea. Consequently, after the deportation, the music of the Crimean Tatars was legalized by the younger generation of Crimeans and was considered distinctly "Crimean Tatar." Amet Bekir explains that from a legal and certain Islamic canon perspective, music among Crimean Tatars, unfortunately, was prohibited, along with other forms of art. Therefore, playing musical instruments was considered unacceptable and sinful until almost the 1930s.

"Our Crimean Roma, or Çingene, took on this role—playing our music in pubs, cafes, during major celebrations, weddings, or other important gatherings. They popularized it and thus preserved and passed it on to the next generation of Crimean Tatars," says Crimean Tatar activist and cultural manager Amet Bekir.

Today, Crimean Roma live in various cities across Ukraine and continue to preserve their ancient traditions, linked to their ancestors who originated from Crimea. They still closely intertwine their everyday and cultural customs with those of the Crimean Tatars. One of the numerous Crimean Roma communities resides in the frontline city of Pavlohrad. Before the major war, the Pavlohrad Roma community numbered approximately 2,500 individuals. Since 2014, many Roma have arrived here from the Donbas region, forced to leave their homes due to continuous Russian attacks a decade ago.

See also

- День Конституції України. Боротьба за права і свободи триває

- Януш Марковський: ром, воїн та батько. Війна навчила цінувати кожну хвилину миру

- «Навіть уборщицею не хотіли брати, бо я — циганка»

- «Коли любиш — можеш і критикувати»: як німкеня Сара Райнке стала патріоткою України

- Табір «Баро Гудло»: як деякі жарти принижують

- Письменник мандрів та дороги. Ким був Матео Максимов для французьких ромів

- Життя ромів в об’єктиві авторки Єви Райської

- Роми в літературі: як їх зображували українські письменники Іван Франко та Марко Черемшина

- Ромські студії: новий науковий осередок при Херсонському університеті

- Не знищені, а ті, хто билися до останнього: 16 травня — День ромського спротиву