Inspired by Shevchenko: Burmek-Diuri, a man who made his dream come true and became the first Romani

He is referred to as the First Romani Writer of Zakarpattia (Transcarpathia). His biography is full of challenges and difficulties that created serious obstacles in his life. These hardships, however, did not prevent the lad to become a writer. Throughout his childhood, Mykola Burmek-Diuri had been roaming with a Roma band, trying to make a dime. Next, he was selling lemons in the Kyiv Metro (undergroing rapid rail); then he worked as a foreman and a builder; and it was not until the age of 17 that he finally managed to get into middle school. As soon as he received his higher education, right out of high school, Mykola started dreaming of getting a chance to describe the world around him. Like back in his childhood years, when he used to ride Transcarpathian suburban trains. His dream was to travel and write books.

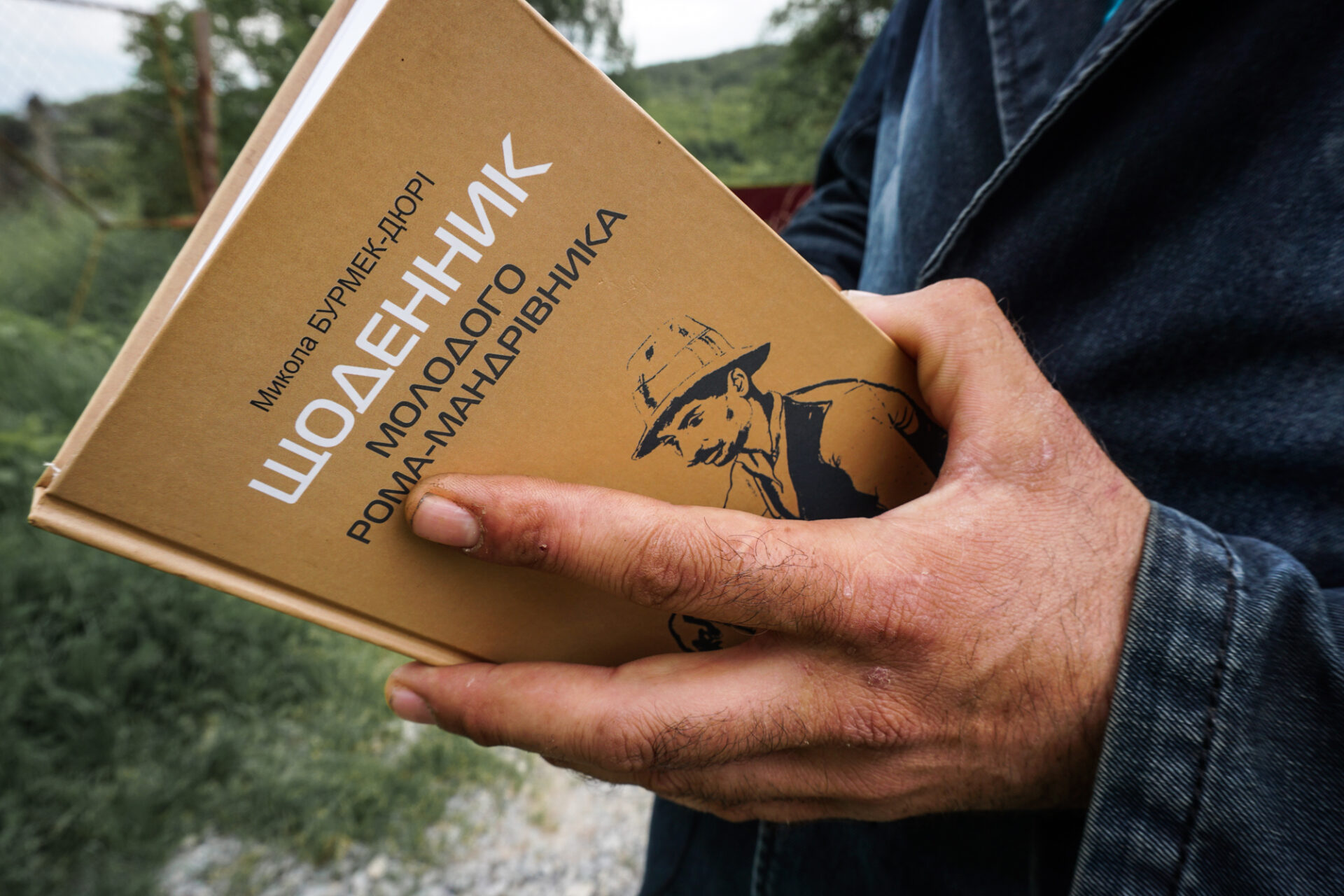

Mykola is thirty-six years old at the moment. He lives in the village of Velyki Komiaty, county of Vynohradiv in the province of Transcarpathia. So far, he has authored five books, namely: «A Diary of a Young Roma Roamer», «Mum Was Right», «The Honour of a Wild Rose», and «A Gypsy and Three Silver Coins». The final one, «Just Shoot Me, I can't stand this!..», was published in January 2024. Writership is a special kind of activity for me, says Mykola. Each word written is a thought which he should always comprehend 'to the bone' before it is brought onto paper. All to the benefit of his future readers.

He considers himself to be a vagabond, as—according to his own words—he was born on the road: someplace between Ukraine and Russia. He is reluctant to talk about his Dad but has most fond memories of his Mum, Mira, a young Roma woman who gave birth to him in an ambulance vehicle. Mira, a disabled woman, was a single Mum who took care of Mykola and his three sisters (another sister died at childbirth). His Dad left the family when he was an infant. Mykola belongs to the Ruska Roma ethnic group who mostly resides across the territory of Eastern and Central Ukraine. He took the second part of his surname — Duri — from his grandad, Laszlo Duri.

In his books, Mykola describes what he sees. The world around him. But the focus of his research is his own life, his family, and his identity.

Mykola comes to the local library in order to gather facts and stories collected from witnesses and records interviews with him. He listens to stories of the elderly. The Romani writer rarely recalls his childhood. He says that he was not that different from other Romani children. But whenever local boys were playing footie or were busy with other kid games. He preferred to stay at home, reading into unfamiliar letters and words in church prayer books and calendars. Then, he put these letters into new words.

As far as Ukrainian literature is concerned, Mykola Burmek-Diuri was most inspired by Ivan Kotliarevskyi and Taras Shevchenko. So when you get to reading his books, you will see that his language is very belles-lettres style with occasional injections of Romani words. After all, one peculiar trait of this Romani writer is that he writes in Ukrainian and not in Romani. Thus, Mykola believes that, as people are read his books, they will be able to find out more about the life of Romanis.

Photo by: Eva Raiska for Reporters

See also

- «Невидимі. Стійкість: минуле і сучасність ромів». Як зрозуміти історію ромів через візуальну культу

- Альфреда Марковська: історія життя і порятунку інших

- «Дивись і не забувай»: 15 років Dikh He Na Bister у Кракові

- ФОТОРЕПОРТАЖ: У Києві відкрили виставку про ромську історію та ідентичність

- «Відновлення пам'яті – роми у Варшавському гетто». Історична екскурсія у Варшаві

- PHOTO REPORT: Events commemorating the victims of the Roma genocide in Babyn Yar

- 2 серпня — Міжнародний день памʼяті жертв геноциду ромів

- Коли допомога — це більше, ніж ваучер

- Антициганізм поруч: як розпізнати упередження у звичних словах і жартах

- Стереотип замість культури: як TikTok спрощує ромську ідентичність