Between education and war: how the occupation has destroyed the education of Roma children

The winter holidays were a month away or so. In Ukrainian education institutions, winter holidays traditionally begin in late December. The holidays are the time of joy and rest, away from studies. For pupils, the holidays are a chance to spend some more time with their family, or tend to their hobby. For many kids, though—particularly to those in the combat zones or in the temporarily occupied territories, holidays have another meaning. Their education was interrupted by war; their access to education was de facto destroyed due to the fact that school buildings have been destroyed—or are operating under the supervision of the occupation forces. The Russian invasion into Ukraine has not only destroyed the ordinary lives of children but also endangered their education, as many schools have switched to remote schooling due to regular air raids and attacks. But the pupils most affected were the ones stuck in the occupied territories. Let us examine this problem by considering two Romani pupils from the city of Kakhovka, Kherson Province (temporary occupied territory—ed.) who have lost the possibility to study as a result of the war. The matter of education of Romani children has always been an acute one. Now, during the war, it has downright exacerbated.

Before the Russian invasion, there were at least 350 Romanis in Kakhovka. It was comprised of two communities: Crimean Romanis and Servs. There were 7 schools functioning in the city, one of which was famous of being regarded as «the Gypsy school», as approximately 15% of its pupils (55 pupils as of 2021) were Romani children. This was due to the fact that the education institution was situated to a population cluster of Crimean Romanis. In addition to the above, there was a youth centre providing informal education in the city: the Romano Tkhan. Total number of Romani children in Kakhovka was about 77. Two of them are the protagonists of our article: Patrina (name changed for confidentiality purposes), a pupil from school No. 4 who, as of the moment of Russia's full scale invasion, was a 9th year student, and Arsen (name changed for confidentiality purposes), a pupil from School No. 6 (‘the Gypsy school’). Arsen's story is a unique one. The boy had studied for two years but then, in 2015, dropped out of school at the age of 8. Later, however, at the age of 14, he decided to get back to school and became an external study mode pupil as he resumed his studies at the level of the 3rd form. As of the moment of Russia's full scale invasion in 2022, Arsen was already a 5th year pupil.

As soon as the city was occupied, the education process at schools halted right away. The occupation forces tried to resume the education process in accordance with the new Russian curriculum but almost no one of the teachers agreed to teach in accordance with it. As Mykhailo Honchar, an education expert at the Association of Ukrainian Cities, says, only 5.5% of prewar teachers agreed to collaborate with the Russian authorities. As per data of this expert, this was the average percentage across the occupied part of Kherson Province. Due to the lack of teachers and educators, restarting of education was scheduled for September 2022. Patrina shares her recollections:

«As soon as it all had started, I stopped going to school at all, and then I was not going to school for like half a year or so. We were in Kakhovka all the time, and then, come autumn, I decided that I had to go to school, but by then now it was already the Russian school».

Besides, the occupation authorities resumed the education process in one school only: School No. 3. Apparently, all the schoolboys and schoolgirls of Kakhovka were supposed to only attend this education establishment only. After the summer holidays, our young lady started to attend school under the supervision of the occupation authorities. As per girl's testimony, many teachers from Russia appeared at her school:

«I had actually been studying at School No. 4 and now we were all transferred to School No. 3. I was unfamiliar with many teachers there as there were teachers from other schools but it was apparent that some of them had come from Russia as you can realise that strong propaganda emanated from such teachers. One such teachers, for instance, was proving to us that Taras Shevchenko had been a miserable creature».

Besides, Patrina tells us that the school she attended served as quarters for the Russian soldiers. So pupils and militarymen were within the same space at the same time. The girl recalls that each morning, before the entered the school, soldiers were checking pupils for prohibited items. The pupil tells us about a case when one of the schoolgirls came to school with two hair binders, one yellow, one blue, and the soldiers made her take them off:

«Soldiers lived in the school shelter and they were either there or on the ground floor. We, on the other hand, studied on the first and second floor whereas the first-graders were on the ground floor. Sometimes, though, we had classes on the ground floor, too—and so we were walking among soldiers. They were young lads, almost all of them, and so they staring at high school girls like, you know, it was not particularly pleasant, I am telling you».

The girl also adds that her grandma forbid her from going to school in occupation, as many teachers had banned pupils from descending into bomb shelters, as they had asserted that an air raid and an air raid alarm had constituted no grounds to interrupt the education process. Besides, Patrina explains the following explanation:

«All of the arseholes in our city got out as there was total lawlessness. I was going to school every morning, and each and every single time there was this one man, and once he tried to attack me. For a certain period of time afterwards, i forwent school, as my grandma was not letting me out. By and large, on the one hand, it was disgusting to attend a Russian school but on the other hand, I was curious as to what were they going to talk about. And then again, there was nothing better to do, as by that time, all of my friends had left Kakhovka».

According to Arsen's testimony, before the outbreak of the full-scale war, he had had an objective to finish his external study mode school and then get into college (university) and become a journalist. The boy very diligently executed each and every assignment from the curriculum and had had an intention to finish school within the ensuing two years; alas, it his efforts did not come to fruition as, come the full-scale war, his education ended:

«Right after the outbreak of the full-scale war, the last I was interested was school. A month later, however, I wanted to find out how things were at school. And so I rang my class tutor up: «the number you are trying to dial is currently unavailable/beyond the coverage area of our mobile network». Then I took some time trying to reach the school headmaster, all to no avail. Later I found out that the school had closed down and that it had been converted into a soldiers' quarters by then».

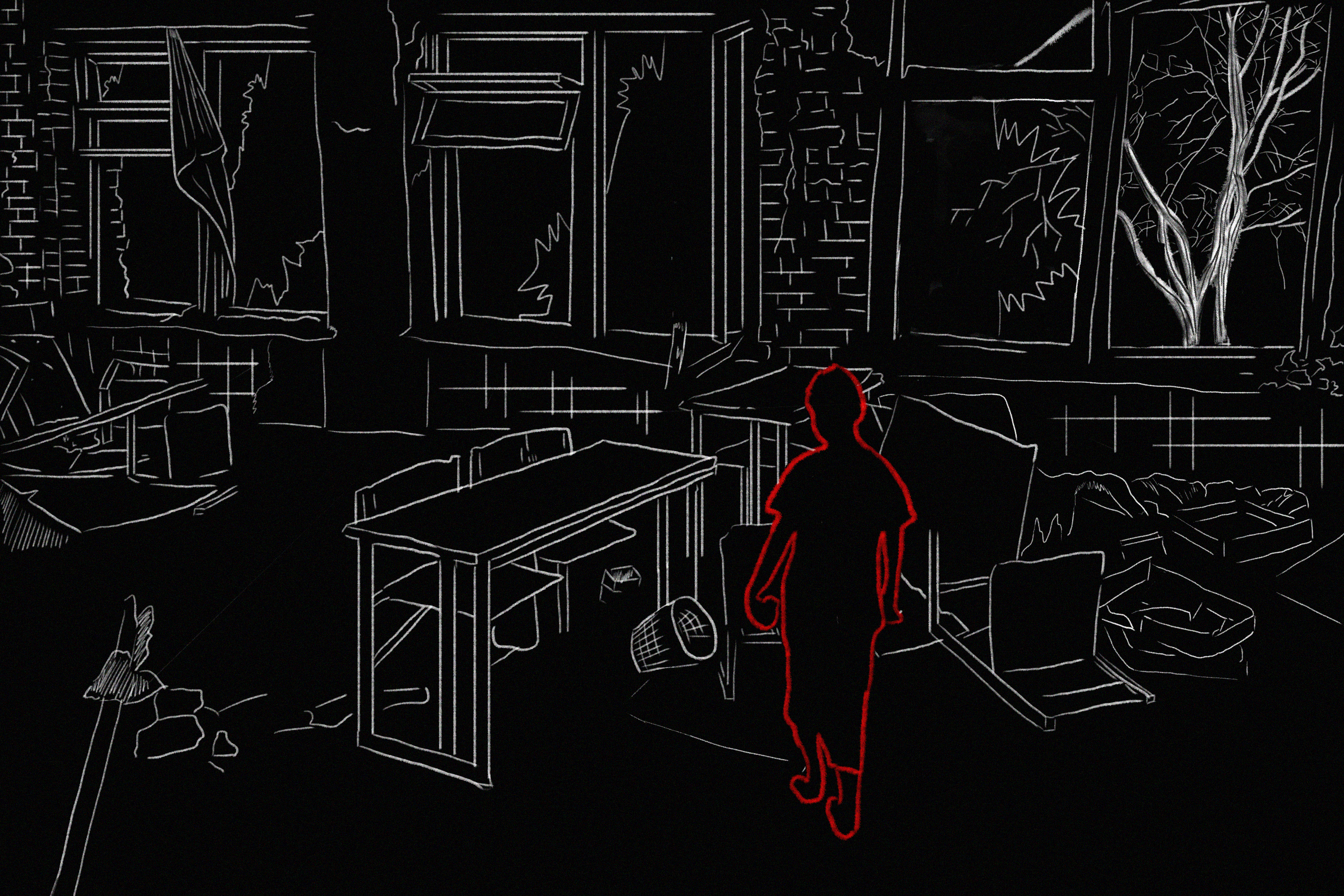

Since 2023, the education process in Kakhovka had been completely halted by the occupation authorities. Even as of now, none of Kakhovka's schools has restarted its education process. Besides, the buildings of certain education institutions had been partially destroyed by rocked attacks or blast waves. This is something that had happened to the abovementioned School No. 6, the so-called «Gypsy school»—and with the Romani centre for informal education, too.

In the summer of 2022, Arsen left Kakhovka and moved outside of Ukraine. He has never resumed his education ever since. Patrina left the occupied territory in mid-2024 only. It took her a long time as she had been unable to recover her documents. Patrina's fate is not unique: there are plenty of Romani children in the occupied territories as of now who, due to various reasons, are unable to leave nor study. The only way they can be engaged in the education process is if they study remotely at Ukrainian schools. However, as noted by Mykhailo Honchar—who is not only an education expert but also a former chairman of the city department of education of the city of Kakhovka—the idea of remote education is a pretty dangerous one. Considering the fact that representatives of the occupation authorities are regularly checking electronic gadgets of local residents for any evidence of remote education at Ukrainian schools, should any such evidence be detected, parents of such children may be stripped of their parental rights.

The situation that has come to exist in the realm of education in the occupied territories is but one of the expressions of the total impact of the war upon the lives of children. Not only has the war destroyed schools but also it has created serious obstacles for the education of an entire generation of Romani children and exacerbated the situation of Romani communities—which, even before the war, had been far from easy. The tragedy of these children's education is a symbol of deep wounds inflicted upon by the war.

See also

- «Невидимі. Стійкість: минуле і сучасність ромів». Як зрозуміти історію ромів через візуальну культу

- Альфреда Марковська: історія життя і порятунку інших

- «Дивись і не забувай»: 15 років Dikh He Na Bister у Кракові

- ФОТОРЕПОРТАЖ: У Києві відкрили виставку про ромську історію та ідентичність

- «Відновлення пам'яті – роми у Варшавському гетто». Історична екскурсія у Варшаві

- PHOTO REPORT: Events commemorating the victims of the Roma genocide in Babyn Yar

- 2 серпня — Міжнародний день памʼяті жертв геноциду ромів

- Коли допомога — це більше, ніж ваучер

- Антициганізм поруч: як розпізнати упередження у звичних словах і жартах

- Стереотип замість культури: як TikTok спрощує ромську ідентичність