Art or a way to survive? How a concentration camp has turned a talent into an instrument of extermin

The 2nd of August is a dark page in the history of the Romani nation. On this day, in a cowardly manner (as becomes dictatorial regimes), at night-time, the Nazis have exterminated the Romani encampment at Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to various estimates, 3,000 to 4,000 Romani prisoners were killed on that day. This tragedy and the horrors of the death camps is the subject of a book by Lidia Ostałowska entitled Farby Wodne (Water Colour Drawings).

The author reveals one of the most tragic and least researched pages of history: the genocide of Romani people during the Second World War. The book focuses not only on the suffering of Romanis in concentration camps but also on their unbroken spirit, on their striving to preserve their identity in the circumstances of the Nazi terror. The Nazis considered the Romanis to be «an inferior race» and that is why this ethnicity, alongside Jews, became the object of persecution, violence, and genocide.

Today, on the Babyn Yar Victims Commemoration Day (the 29th of September), we shall discuss the book and the history it depicts.

Violence registered in tender colours

Before we start telling our story, let me familiarise you with a person called Joseph Mengele. He was an SS physician who conducted violent, inhumane experiments using prisoners of Auschwitz-Birkenau as his test subjects which these people, quite often, simply did not survive. If there were any survivors, this «physician» simply sent them into the gas chambers. He was referred to as the «Angel of Death» as he dealt with selection and screening of prisoners. Anyone ill or exhausted was detected right upon arrival of the train and killed in the spot. Anyone injured as a result of hard labour had a chance to receive a lethal injection from Dr Mengele.

Photo: Joseph Mengele (source: Wikipedia)

The «scientific interests» of Mengele mainly included genetic experiments. He sought to find that special gene which would enable him to make the Aryan race even more «pure». Twins, Romanis with bright eyes and light-coloured skin were the particular «passion» of Mengele, a devoted fan of eugenics.

Why, though, do we pay so much attention to one of Auschwitz’s physicians? Because he it closely related to all the characters in this book, Farby Wodne.

So, Auschwitz-Birkenau. Cynically even rows of wooden barracks for cattle—inhabited by humans, though—hundreds of them stuffed into a single room. Under the burning sun. Under droughty winds. Forced labour. Malnutrition. Thirst.

Photo: one of the barracks in Auschwitz-Birkenau

And amid all of this stands a girl named Dina, painting a picture on the wall of one of the barracks. Dr Mengele notices the talent of the young Jewess and entrusts Dina with a special job: to paint portraits for him.

Those are supposed to be water colour pictures only. After all, it is only water colour that can relay miscellaneous shades of colours. A photo film makes the image rough and unclear. What a sensitive person he is, this «physician»… He wants to make faces appear realistic in the pictures. Faces of people whom he will later kill.

It is important. Important to whom? Important why? For the sake of his «hyper-important» cause, Mengele is ready to buy paint, canvas, and wait two weeks for the next portrait to be ready.

An artist who paints future dead people

Dina Gottliebová, a Jewess, a talented artist whose «art» has saved her from imminent death. Chosen by Doctor Mengele, she commences her «creative work».

Photo: Dina Gottliebová (open source)

«I had no idea who he was and what kind of experiments did he conduct. I watched him photograph Gypsies, I saw how unsatisfied he was. Next, Doctor Lucas introduced me and told him I was a painter who can paint really good portraits. He explained to me that a colour photo lacks perfection whereas here, it is important to convey real shades of the colour of the skin», says Dina, as quoted by the author of the book.

So how did this portrait-making go about? Dina entered a barrack where she saw a girl «clad in an exquisite motley neckerchief». And so the work began which lasted two to three days.

Next, Dina tells the story of a woman which impressed her: «In this miserable-looking crowd, there was a young Gypsy girl which stood out, wearing a nanking neckcloth. I took the neckcloth off her neck and tied it around her head. I asked her to smile. She replied that her two-month old daughter had just died, unable to survive without breastmilk. I stopped asking her for a smile».

A smile… How difficult it is to comprehend this request. On the one hand, it is pretty cynical to ask for something like that, particularly addressing your fellow prisoner. On the one hand… From what other standpoint can we view this situation? How can we explain this wish to create a relaxed atmosphere, to make friends with someone you know will soon be killed and whose death you are implicit in?

I do not want to judge Dina. It is amazing that her talent has saved her life. In such inhumane conditions, one will do anything to survive. There is, however, something that surprises me: the thing that Dina regarded this painting process as a form of art. Considering the fact that the «models» just were not able to ‘decline the offer’, neither did they enjoy the process or the outcome. But we shall get to that «artistic» component a bit later.

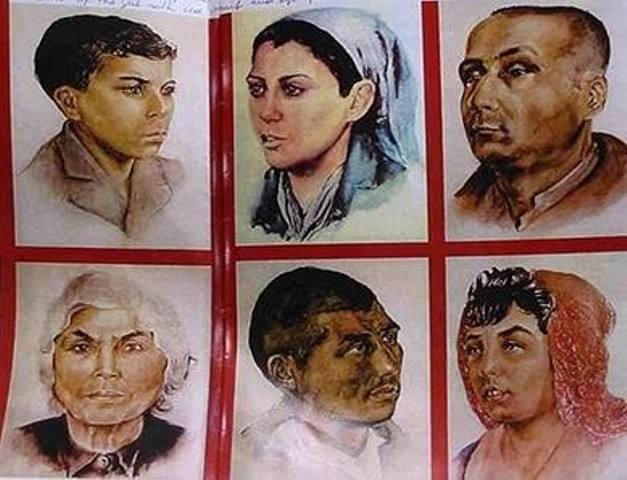

Photo: paintings by Dina Gottliebová (open source)

What about the doctor then? This is how Lidia Ostałowska describes his participation in the process: «Doctor used to check on the progress from time to time. Normally, he would avoid touching the prisoners; this time, though, he personally tied the blue neckerchief behind the Gypsy woman’s ear. He opened it. An important element for racial studies». Rather cynical, too. It seems to me that I am overusing this term. I cannot put it otherwise though. Disenfranchised people, objects of scientific studies, deprived of all rights, forced to submit while parts of their bodies are displayed for the sake of the purity and clarity of research.

As far as Dina is concerned, she considers the time thus spent to be a blessing: «As I was working in the Gypsy camp, I did not have to stand at roll calls; I did not have to do anything at all, in fact, apart from painting. When Mengele went to have dinner, he grabbed some food for me, too. This was the only portion of time spent in Auschwitz when I felt I was a human being. I took my time to paint».

Photo: personal items of people imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau. One of the exhibitions in the camp. Photo author: Daria Vorona

In addition to this, Mengele also explained to Dina the peculiarities and nuances of Romani appearance. «He showed me how various types of Gypsies differ from each other. How the Aryan hairline is aligned with the eye level. How the blue colour of Gypsy eyes differs from the blue colour of Aryan eyes. Which colours are the deepest ones».

Dina then suspected that her works would be used in a book, as illustrations. Mengele carefully inspected each of her pictures. Sometimes he asked for some adjustments, and then he took the picture away. He hid his treasures in a cabinet, under lock and key, as he was afraid of competition.

So, let me sum it up. Dina was saved by her talent. She was «working» as an artist. She registered the faces of Romanis in order to be able to see ethnic peculiarities. She received «bonuses» from Mengele: no forced manual labour, better nutrition and clothes.

The ‘non-pictorial’ life of Romanis

In Dina’s pictures, Romanis are clad in colourful neckerchiefs. How «colourful» was the reality of the camps for them though? Spoiler here: the picture was quite different. In fact, the degree of depressiveness and anti-humanity was unimaginable.

Rudolf Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz Concentration Camp, deliberated in his autobiography: «Despite the hard conditions, the majority of Gypsies, as I have been able to understand, have not suffered much in their incarceration, apart from the fact that their thirst for voyaging was paralysed». Yeah, right. Why doesn't one just stop suffering? The hunger, the lack of hygiene, the slave labour, the restrictions on movement, rags instead of clothes, and ultimately: being murdered. Not a big deal, right? Why suffer? (Obvious sarcasm here — ed.)

Another quote, about the «not so much of suffering», to crown it all: «Over nine hundred deaths in the Gypsy camp, month after month, from typhus, diarrhoea, scarlet fever, and diphtheria. It was here that most of Birkenau’s children perished. Having forgotten what food is like, they were not even asking us about it; everyone just wanted something to drink. There was nothing we could do, neither threaten nor beg, that could dissuade them from drinking dirty water. When they became too weak to walk, they got off the bunk, silently crawled toward the buckets and drank the water used to wash the floor».

Photo: a fragment of an exhibition at Auschwitz-Birkenau

Well ain’t that comfortable? Ain’t that just normal? "The only thing they missed was the possibility to voyage", right? I realise that this is just what the Nazi ideology looked like, so neither Rudolf Höss nor anyone else could say how horrible life was for the Romanis (and any other inmates, too) in the concentration camp. But I cannot just keep silent and not react to their attitude, to the normalisation of that hell, to the fact that Auschwitz-Birkenau and camps alike even existed at all.

Another thing worth noting is the position of medical doctors who worked inside the Gypsy encampment. One of them, in particular, was Dr Epstein who gave the following testimony at Höss's court hearing: «I recall my first impression of the Gypsy encampment. I thought I found myself not in Europe but in Sudan, somewhere in the African hinterland». So that is how «normal» and «common» were those conditions the Romanis ‘enjoyed’. Dr Epstein, though, was not taken aback by that. He operated the laboratory in an experimental barrack.

Does the art (not) belong to the artist?

So, what about Dina and her portraits?

As they fled, the Nazis blew up crematoria and burnt related documents. There were several pictures that were preserved due to the fact that they found themselves in the hands of a private owner whose relatives handed them over to the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum.

Next, Dina Gottliebová launched the process of return of images. It took a long time of correspondence exchange and a number of court hearings for Dina to be able to recover those portraits into her possession. She is convinced that «everywhere, apart from totalitarian states, the paramount principle is recognised, i.e.: that a work of art belongs to the artist who created it». Here, though, another question arises: should we even consider these portraits to be art at all? Created in prison, under duress exerted both upon the author and the characters in the pictures—none of whom consented to be painted. No one was willing to sit for portrait. They were just following orders.

Countering Dina's arguments, the museum curators note that those pictures are evidence of unspeakable cruelty, cynicism, and mass murder of Romanis, so they have to be stored where those atrocities were committed. Of course, Dina and her lawyers disagreed with that statement…

You can read more about this confrontation in the book itself, Farby Wodne (Water Colours). Now, let us think on it. Are these portraits really art? Can we even talk about copyright or suchlike? And why does Ms Dina have such a need to own them? One can assume a lot about the motivation the painter has. But only she knows the truth. I personally wouldn't want to have such memories (or mementos). I wouldn't like to be watched by death from the watercolour canvasses. Even if it were in a city exhibition hall where I reside, as Ms Gottliebová would prefer.

Photo: the territory of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp

Photo: the territory of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp

The deadly watercolours

So, here is Farby Wodne (Water Colours), a painful book about horrendous events—yet one which you just cannot abandon. One just wants to reach the final pages as soon as one can—reach a place where this hell finally comes to an end. But that never happens. And the book carries its flashbacks into the realia of today. But one needs to read it, one needs to know.

The author asks: «What does an artist feel under such pressure? The art should not serve the cause of extermination of people. What if it does, though, and what if it brings satisfaction nonetheless? Simplified to a photograph, to a trade—yet to one that helps a person survive. How can one deal with that?»

Besides, new questions arise, too. How did the executioners turn out to be «simply physicians» caring about the health of the nation? How come the survivors (Roma people including) found themselves in a situation whereby they had to prove the fact of their suffering? How can one solve a dilemma: are pre-murder portraits art or are they evidence in a criminal case? And does this cynicism simply have no boundaries?

This can be best summarised by a quote from the book: «The wheels of justice omit the murderers. But nothing stops them from finishing the victims».

See also

- «Невидимі. Стійкість: минуле і сучасність ромів». Як зрозуміти історію ромів через візуальну культу

- Альфреда Марковська: історія життя і порятунку інших

- «Дивись і не забувай»: 15 років Dikh He Na Bister у Кракові

- ФОТОРЕПОРТАЖ: У Києві відкрили виставку про ромську історію та ідентичність

- «Відновлення пам'яті – роми у Варшавському гетто». Історична екскурсія у Варшаві

- PHOTO REPORT: Events commemorating the victims of the Roma genocide in Babyn Yar

- 2 серпня — Міжнародний день памʼяті жертв геноциду ромів

- Коли допомога — це більше, ніж ваучер

- Антициганізм поруч: як розпізнати упередження у звичних словах і жартах

- Стереотип замість культури: як TikTok спрощує ромську ідентичність