The Melody of Mother Tongue: How Romani children get to know themselves through words

How many stereotypes about Romanis do you know and what kind of stereotypes are these? What about culture and traditions? Today, we are going to get you acquainted with a person who, through her work, proves the absurdity of bias and opens the world of Romani language to the attention of society. Anastasiia Tambovtseva is an ethnic Ukrainian who teaches the Romani language, has a popular blog and is just convinced that Romanis are «normal and adequate people». So today, we shall discuss learning the language, integration into the Romani community and the attitude of the Ukrainian community.

«I have found out about the Romani language and about the challenges which even those linguists face who work with Romani language»

–I think this is a bit of a generic question but let us still begin with it. How come an ethnic Ukrainian has become involved with Romanis? Where does this interest come from? What does your present-day work consist in?

– Yes, this question is really one of the most popular ones—but the answer is different each and every time. So, back in 2018, I decided to learn a new language, and to make it something that would be useful to society. So I was in the process of selecting a language to learn.

I was indeed sitting, picking and choosing, as a matter of fact. My first choice was Turkish, as there are plenty of people in Ukraine who deal with Turkish. After certain considerations and reconsiderations, however, I came to a conclusion that I would be able to use this language only in business situations.

So, I decided to forgo Turkish. Next, I somehow thought about Romani. I was not afraid of Romanis but, let us say, I was not much of a fan of the culture. I did not follow it. I had no Romani friends.

I did consider the Romani language nonetheless. Back then, I knew nothing about the diversity of dialects; I thought this was a unified language. So I decided to listen the sound of it, to know what kind of a language it is. The first thing I did was, of course, open Google Translate and type «Gypsy language». My search yielded no return. I typed the same thing in English—to no avail. Romani, Romany—nothing. That was a bit of a shock to me.

This impacted upon my attitude quite a lot. I could not understand why people had this careless attitude towards their own language. They did not even make any effort to put it into Google Translate. I mean, that was an indicator to me: if I love my language, if I respect my culture, I will, of course, make sure it is available on top apps. Nothing like that was present here.

– Those were your first thoughts. Has anything changed since? We know, after all, that the Romani language is overall an oral one. There is no unification and there are many dialects… Has an understanding come why was it not on Google? What kind of work was supposed to be done in order to make sure Romani was on Google?

– Well of course it did, as I found out the reason why it was so. I have found out about the Romani language and about the challenges which even those linguists face who work with Romani language. I also got to know what historical prerequisites and reasons were which caused such an attitude in Romanis themselves towards their own language.

«When a child approaches you and asks you to teach it, one just cannot refuse»

– And so, you undertook to learn Romani. What was your next step?

– I got acquainted with Romani families. The children from the first family attended school but had certain gaps in their knowledge due to their poor command of the Ukrainian language. Those were the children whom I started to teach, to help, to explain certain school-related terms. It was a bit of a private tutorship on my side.

Later, I got acquainted with other families, too, whose children did not attend school at all. As soon as I found out about that, as soon as I saw them, I decided that I would perhaps spend an hour a week to teach one or two of those kids. I saw their desire to learn to read and write. Later, as soon as the children found out that I wanted to teach them, they approached me and said: «Will you teach me how to read?»

And so, when a child approaches you and asks you to teach it, one just cannot refuse. You just understand that the kid in question does not attend school, that his or her parents are illiterate, that all of her relatives are illiterate, that there is just not even a pen and a sheet of paper at his or her home, as they do not need anything like that, as they cannot write. What kind of hope do such children have?

As soon as I decided to teach them, I picked one or two children BUT the first lessons were attended by 5-7 kids already. Overall, there were many more children willing to learn. I alone was physically unable to handle all of them in the course of a lesson. Secondly, we just did not have an adequate place to study. We had a small studio which I leased as an English teacher. Sometimes my classes took place at children's homes but those were homes with no adequate conditions. Sometimes we had lessons in the park on benches.

This was the experience we had. And it was for the sake of the Romani children that I have learnt the language.

«I have never met Romanis who would be unwilling to learn—and that applies to any other ethnic group, too»

– How did the integration into the community take place? Were there any disputes? Did your views always align? After all, the cultures are similar but different at the same time. Besides, our society treats Romanis with a bit of caution, if you allow me to put this mildly. There is a stereotype that Romanis are lazy and just do not want to learn.

– As far as Romanis not willing to learn, I have never met Romanis who would be unwilling to learn—and that applies to any other ethnic group, too. We can always find a person who just does not want to learn. I mean, this is a phenomenon not typical to a minority, an ethnic group as a whole.

I did not experience much of a barrier. I cannot imagine what obstacles can there be if you work with normal, adequate people. I was, of course, never accepted nor perceived as entirely ‘one of them’. There was, of course, a bit of a distance—that, though, is a normal distance which exists between all people, between all ethnicities.

Romanis are, as a matter of fact, very hospitable. I mean, you just cannot come to their home and not be treated to a meal. In Ukraine, you will always be offered tea. In other countries—Balkans, for instance—that would be coffee. And if you decline the offer, the host might get offended. How come, after all, the guest did not drink tea! What a shame!

So I was accepted and people shared information with me. I had a lot of questions about their language. I asked them to explain why was this pronounced this way and not that way etc. And they did indeed explain it to me, as native speakers, so I did not have to further try to understand the architecture and mechanisms which I was trying to untangle.

As far as integration is concerned, I have never intended to become a teacher of Romani language. Even with those children, I initially learnt letters, sounds, we painted something, we learnt just how to hold scissors or a pen.

That said, I never intended to teach them Romani, as this was their mother tongue, and they speak it very well. I was only using my command of their language in order to become a better teacher for them. Thanks to the fact that I learnt their language, I was able to teach them Ukrainian, as the issue consisted in the fact that children did not understand Ukrainian at school.

The more I studied Romani, the more I used it in my conversations, the more Romani language assignments I managed to introduce during our classes. Certainly, I wanted to give Romani language classes (that is, written Romani language) to its native speakers. And this is what I am doing at the moment.

«My objective is not to teach Romani but to teach in Romani»

– Why so? After all, native speakers know their language anyway…

– It is my opinion that the basics, the foundations of written language, the reading skills are something that must be ‘pre-installed’ by your mother tongue, by the language of your heart.

What kind of a situation did Romanis find themselves in? Firstly, even if they learn how to read and write, they learn how to read and write in the language which they use at school. If they live in Ukraine, that would be the Ukrainian language. So it appears they can learn how to read and write in just about any language, save from their own. After all, everyone around tells us that our (Romani) language is not a written one, that you can neither read nor write anything in it.

Within such an outlook, literacy is viewed as something alien, something that is just not natural to your culture. But if you see that your mother tongue can be used to read and write, this gap—or abyss—disappears.

I can just share with you what I have seen during one of my lessons. Every time I tell this story, I have shivers running down my spine. Once upon a time, me and my kids, we were training, learning letters and suchlike, and I told them: «Oh, you already know these letters. Now we can write some words in Romani. Let us try then».

And then I wrote two letters on the blackboard. These were words «dorov» and «dad». And so these kids, they just sat there, staring at the blackboard, and they were so surprised, so amazed, almost mesmerised. I failed to understand what had just happened. And then I understood that, on the one hand, they were surprises and amazed—as, for the first time in their lives, they saw and realised that one could just write something in Romani. I suspected, though, that there was more to it. Later, I read about this phenomenon.

The children are bilingual. And, same as each and every one of us, they love seeing something written in their mother tongue. But in this particular case, not only do they see their mother tongue in writing; they come to realise, for the first time in their lives, that one could write something in their mother tongue in the first place.

So, my objective is not to teach Romani but to teach in Romani.

«Now, all of my plans are related to this: to grow and develop as a Romani blogger»

– What about Ukrainians? What did Ukrainians say about that? How did they perceive this interest of yours and this work of yours? I, for instance, hear people say that I ‘do not have anything better to do’.

– Well, no one has ever told me to my face that I had ‘nothing better to do’. People do write, though. But all of this began much later, not until I went online with that, onto social networks. It was there that they started commenting like «you've got nothing better to do».

There was, of course, a bit of a surprise. Why are you involved in this? What are your getting out of it? But I felt some kind of respect, too—as the people did understand that the cause was important and that my work was important, too. People have always wished me well, and I felt their sincerity at all times.

– What kind of challenges do you face in your work today? What kind of assignments to you have, what kind of plans? What do you want to do and what perhaps prevents you from doing that?

– Let me put it like this: today’s tasks differ from my initial tasks a lot. Back when I had started all this, I had no plans at all to become an influencer in the Romani community. Now, of course, all of my plans are related to my growth and development precisely as a Romani blogger. I am aware of the fact that I would like to crate more content and enhance its quality.

It is quite difficult to make this step. After all, I have always treated my work in the Romani community as a bit of a socially useful hobby. Now, it has grown into something much bigger. Now, I have to make it into a cause of my life.

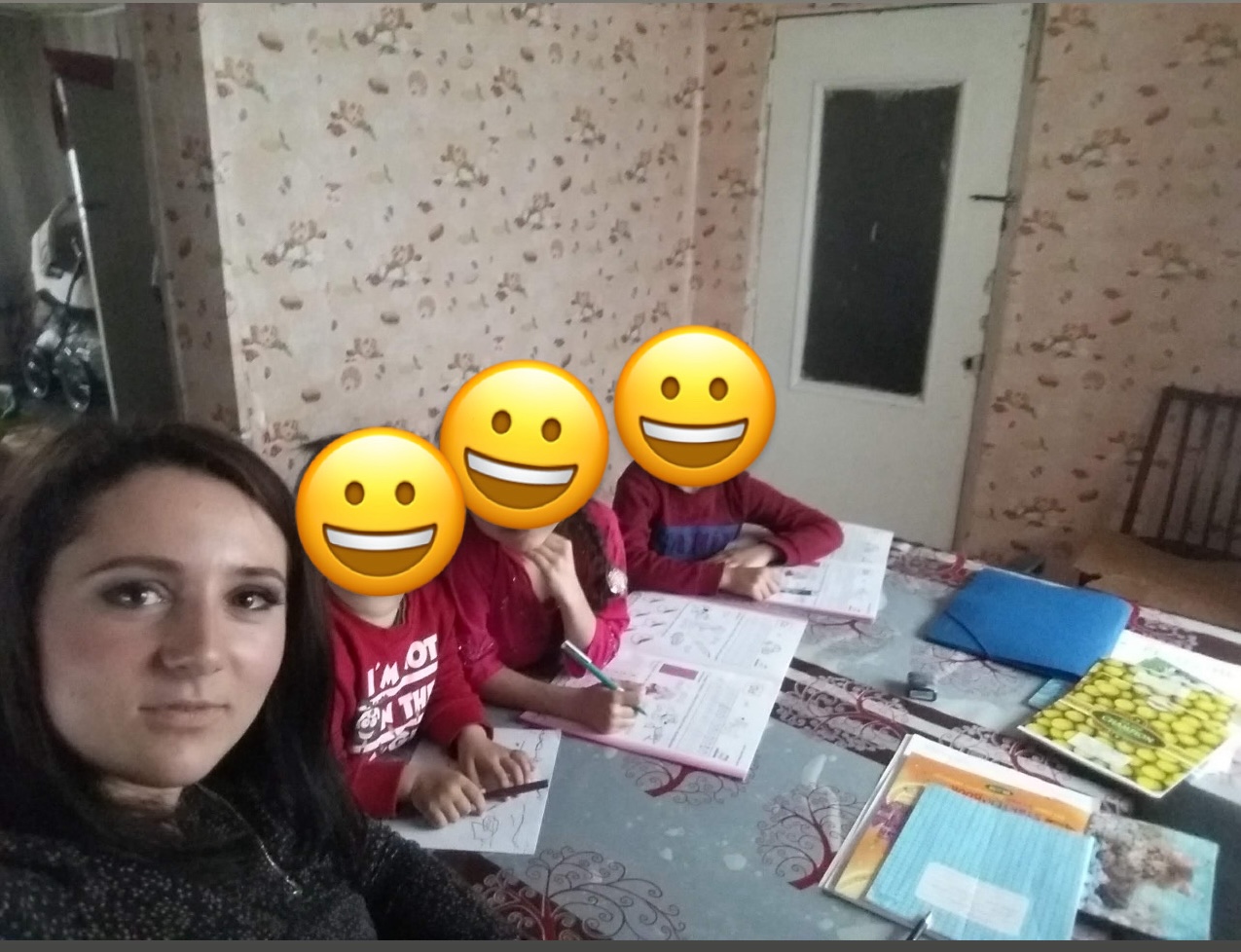

Photo from the personal archive of Anastasiia Tambovtseva

See also

- Roma in Pixel: Stories from the Front

- Ром Сергій Вишановський: «Моя нація теж тут, на цій війні»

- Шелтери як шанс на новий старт: чому вони важливі для ВПО в Україні

- AURA: платформа для самоорганізації і захисту прав ромської спільноти за кордоном

- Ромські активісти – про новорічні та різдвяні традиції

- Репортажистка Єва Райська: «Через звичайні людські історії я хотіла показати глибші процеси».

- Новий центр підтримки ромів у Сумах: хто отримає шанс на освіту

- Письменниця Тімея Шрек: «Життя так склалося, що повертаюся до коренів».

- Танцівниця Вікторія Чорна: «Саме ромський танок допомагає людям просто вижити»

- Громадські активісти і дослідники — про ромську мову, перспективи розвитку та загрози