Something should be left in the past: the stereotyping of Roma in classical literature

This is a classic! We hear it everywhere. Authors of enthusiastic reviews may even raise their eyes to the sky, click their tongues, and make a characteristic hand gesture. But what lies behind this classicism? What does literature, which has become a model, teach us?

Disclaimer: we do not deny the achievements of Ukrainian authors. We respect the colossal work done under the terrible pressure of empires. Thank you for laying the foundation of the modern language.

The purpose of this text is to show that something should be left in the past.

Now, about history. In pedagogical universities, literature teachers are taught the important principle of text analysis: taking into account the historical context. However, it somehow gets lost on the pages of lecture notes. In life, though, we have...

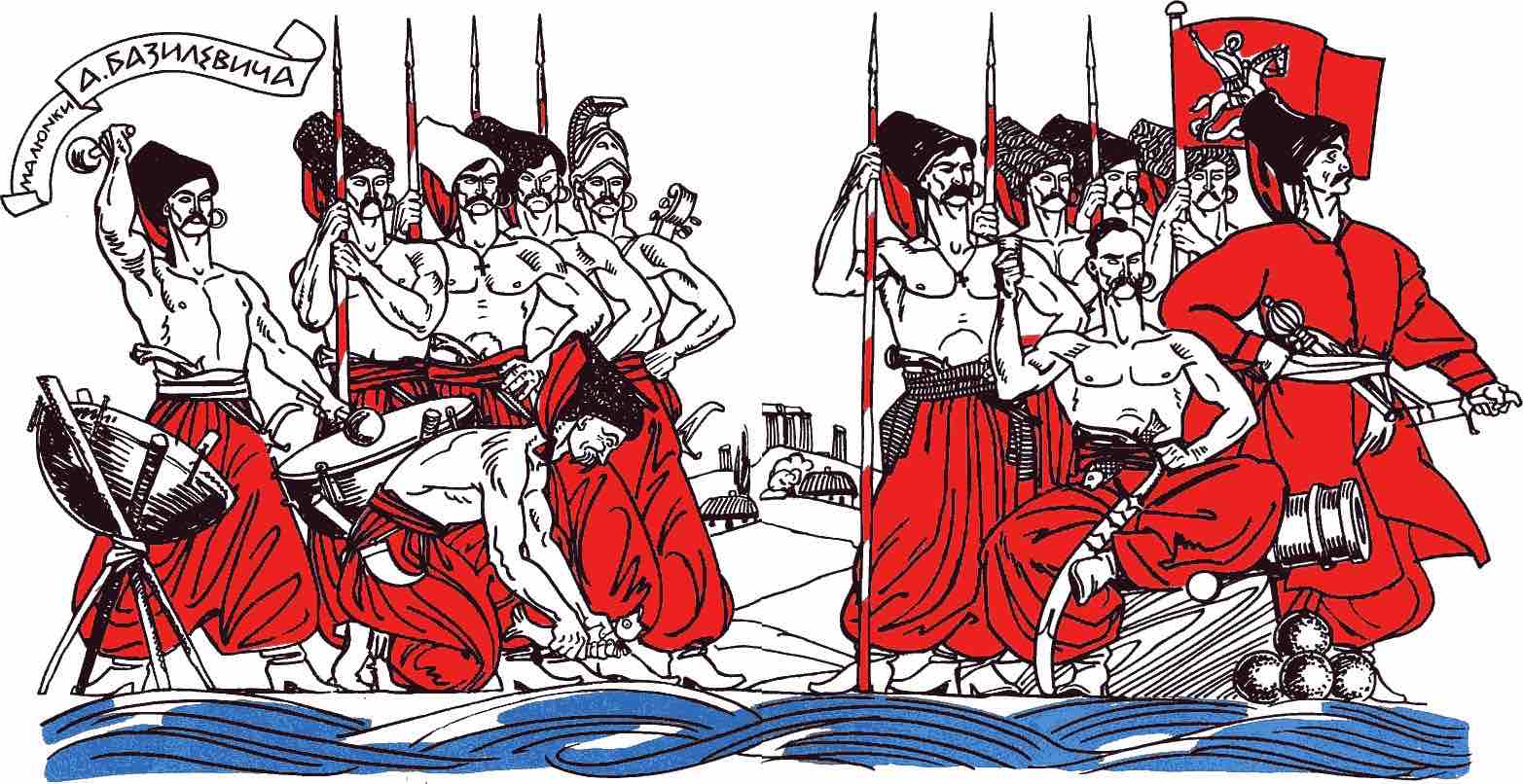

So, let's remember classical literature. And let's start with the favorite of children and adults - Ivan Kotliarevsky and his famous "Aeneid."

Immediately - a few quotes below.

“School students in the open windows sang,

And Gypsy women capered with a bang,

Blind kobza players were there, too…”

"Aeneas, noster magnus panus

And famous rex Troyanus,

Who sailed the seas like some Tsiganus…”

“How will the world judge us?

A Gypsy band contemptuous?

More cowardly than Jews, or worse?”

“Walked all around without excuse

Like Gypsies in the altogether.”

Enough, probably, to understand the reference.

So, what image of Roma does Ivan Petrovych paint for us?

Cheerful vagabonds without a permanent residence. Nomadism - something shameful. And no moral values.

So, how do you like such a person? Do you want to have someone like that among your friends?

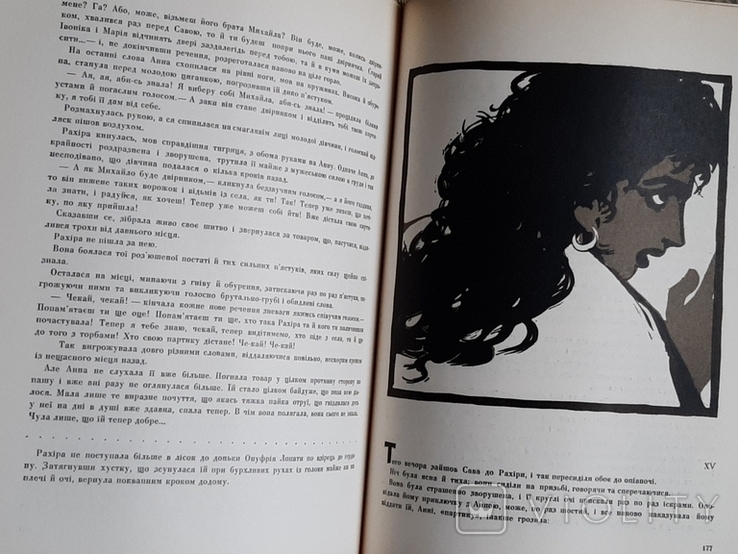

Moving on. Progressive Olha Kobylianska and her "Zemlya" (Land). (I confess, she is one of my favorite authors. But despite my thorough readings of her texts, I did not notice the "Roma trace" - author's note.)

So, what do we see?

One of the main characters, Rahira, is a half-Roma (the texts use the word "Gypsy" and its derivatives, but in this article, we consciously replace it with the more widely used term "Roma"). Her father is a Roma who had a Ukrainian wife. However, he abused alcohol and drank away his wife's land.

Rahira resembles her father: dark-haired, lazy, and also cunning, charming, and deceitful.

The Roma woman outside the tribe is a strong woman who drives Ukrainian men crazy.

Only Roma are endowed with such traits, right? Confirmation can be found in another work, "Early Sunday Morning I Was Gathering Herbs.”

In the story, the father sneaks his child out at night and offers her to the wealthy Ukrainians. Even when raised outside the traditional environment, the Roma maintain their distinctiveness, impermanence, and freedom from settlement. In the end, the heroine settles in the forest as far away from people as possible, suggesting that one's genes have their influence.

In Olha Kobylianska's works, the Roma remain true to their traditions, whether they grew up within their community or outside of it. They aspire to freedom from responsibilities and sometimes engage in theft from Ukrainians.

Why is such an image present in our literature? It originated in folklore. Here are a few examples of proverbs:

- A Gypsy won't pass by for free.

- A Gypsy sings songs but grumbles in life.

- A Gypsy seeks ways to deceive others.

- A Gypsy manages to live by cunning.

Everything that deviated from the established conception of the world triggered suspicion and condemnation. There was a need to work hard, create families, have children, attend church every Sunday. Anything that didn't fit into this concept was considered bad and wrong. Even if Ukrainians did not adhere to these views and lifestyle, they were ridiculed and labeled as "Gypsies," "Jews," and so on.

Traits such as thriftiness or love for freedom were reduced to absurdity, becoming greediness associated with all Jews or revelry linked to Roma. This prejudice infiltrated the pages of literary works, presenting stereotypical, generalized images that were easily understood by every reader. Such notions were commonplace for that time.

Here again, the historical context comes into play. Back then, it was like that. It was considered normal, just like serfdom, the lack of women's rights, arranged marriages by parents, and many other practices. However, today we assert that all people are equal in their rights and opportunities. We make jokes about slavery in the context of hard work without days off, emphasizing that it's not normal.

Times have changed, perceptions have evolved. But for some reason, the opinion about Roma persists. Classical literature is sometimes used as an argument that all Roma are the same.

Another argument: this is our Ukrainian tradition. Okay. Then let's agree with the Moscow tradition of calling Ukrainians "khokhly" and "malorosy." Moreover, Chekhov and Gogol (who were of Ukrainian origin, by the way) wrote in this way. Does it mean it's true?

What do you say? No? Offensive? Then why is "Gypsy" not considered offensive?

Reality has changed. And today's context is different.

Yes, reading the classics is necessary. To see those terrible periods, to understand how much our people had to overcome. To understand history. And the realities of life. To prevent such things in the future. Including discrimination based on ethnic origin.

See also

- To do list до 30-річчя: вилучіть зі списку пункти про стереотипи та ромофобію

- Romanis. Remembering the Holocaust Survivors

- "The feeling of being under the crosshairs never left me": Kherson resident on life under occupation

- «Невидимі. Стійкість: минуле і сучасність ромів». Як зрозуміти історію ромів через візуальну культу

- Альфреда Марковська: історія життя і порятунку інших

- «Дивись і не забувай»: 15 років Dikh He Na Bister у Кракові

- ФОТОРЕПОРТАЖ: У Києві відкрили виставку про ромську історію та ідентичність

- «Відновлення пам'яті – роми у Варшавському гетто». Історична екскурсія у Варшаві

- PHOTO REPORT: Events commemorating the victims of the Roma genocide in Babyn Yar

- 2 серпня — Міжнародний день памʼяті жертв геноциду ромів